THE ORDINAЯY MOMENT

A report on the exhibition “The ORDINAЯY MOMENT” at the Budapest Photo Festival 2025

Introduction

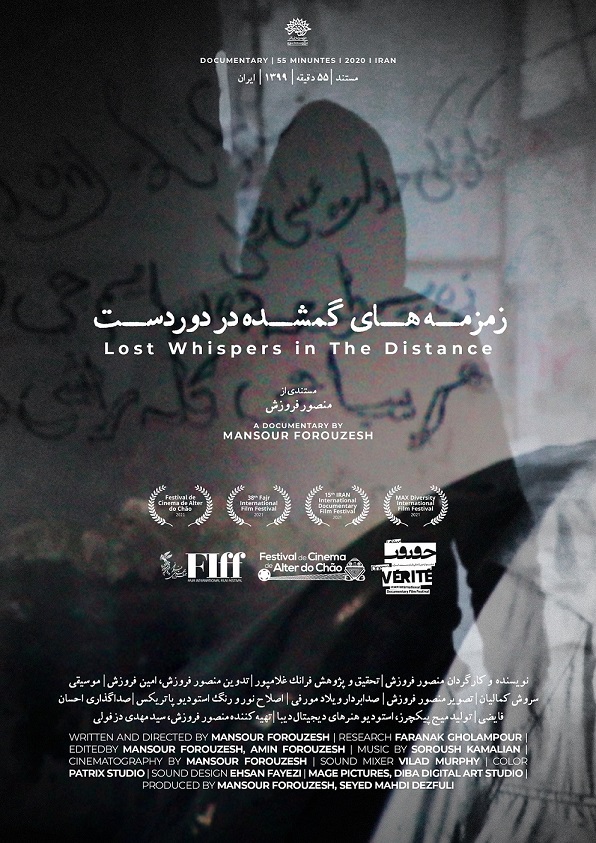

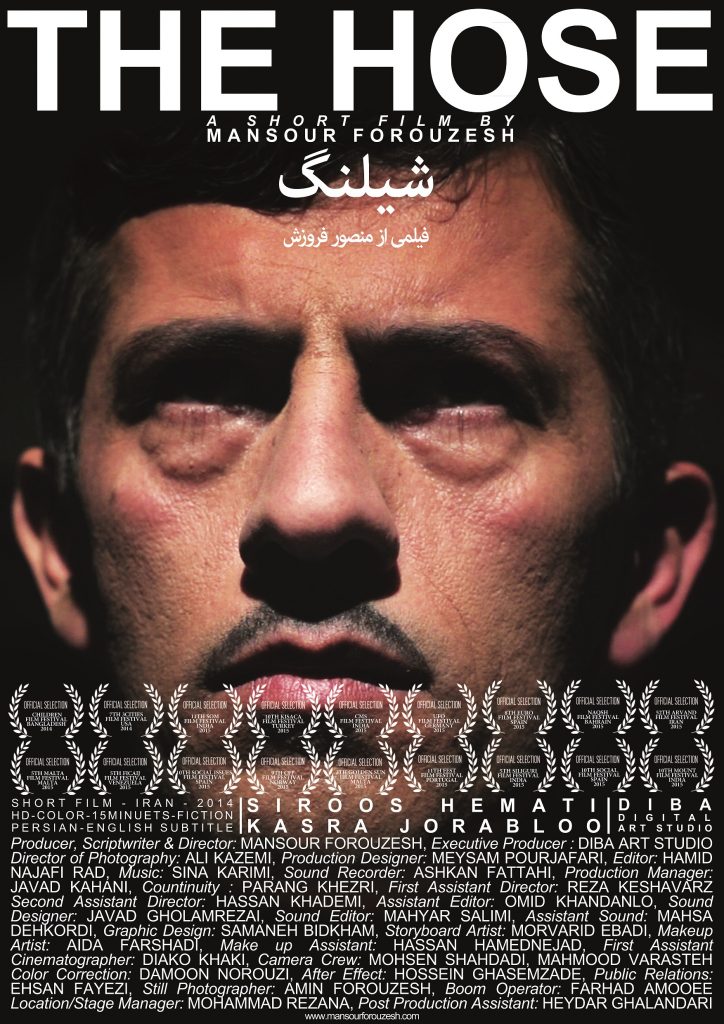

The ORDINAЯY MOMENT is a group exhibition presenting works by Iranian photographers at the Budapest Photo Festival 2025. Curated by Mansour Forouzesh, the exhibition centers on storytelling as a fundamental mode through which photographers engage with and narrate the world. Rather than foregrounding stylistic unity or thematic consistency, the exhibition proposes a relational approach, emphasizing the lived photographic practices of its participants and their sustained engagement with everyday reality.

The exhibition deliberately focuses on photographers whose work remains largely absent from dominant institutional, market-driven, and festival-oriented circuits. These are practitioners whose artistic production is neither marginal in quality nor derivative in form, but structurally peripheral within contemporary systems of cultural validation. In this sense, The ORDINAЯY MOMENT can be situated within a broader inquiry into what may be described as independent middle-class art: cultural practices produced outside elite institutional frameworks, yet marked by conceptual rigor, narrative depth, and sustained personal commitment.

Rather than articulating a single thematic proposition, the exhibition constructs a composite narrative of everyday life in Iran. This narrative emerges not through representational consensus, but through the coexistence of distinct artistic positions—each shaped by the photographer’s social location, lived experience, and relationship to the act of image-making itself. The exhibition thus unfolds as a multi-layered dialogue between individual modes of seeing and broader questions of representation, visibility, and meaning.

This report examines The ORDINAЯY MOMENT through conversations with the curator and participating photographers, situating the exhibition within contemporary debates on narrative, institutional visibility, and independent artistic production.

Following the First Spark: Paths Outside Institutional Formation

A defining characteristic of the photographers presented in The ORDINAЯY MOMENT is the absence of a linear or predetermined trajectory into professional art practice. Like many photographers working outside institutional centers, their engagement with photography often began as a contingent encounter—a spark ignited at a particular moment, rather than the outcome of formal artistic training.

Photography initially functioned as a means of orientation: a way of making sense of the world when language proved insufficient. Over time, this spark was sustained through diverse tools and formats, ranging from mobile phone cameras to analog and digital systems. The heterogeneity of image-making devices visible in the exhibition reflects not technological eclecticism, but a continuity of attention across changing material conditions.

Universities, social media platforms, theatrical environments, and journalistic contexts served as formative spaces in which photographic practice gradually took shape. These were often non-art institutions—sites where visual expression emerged as a response to structural absence rather than institutional encouragement.

Curator Mansour Forouzesh recalls his own experience studying at a non-art university, where a film and photography club provided an entry point into artistic practice:

“My relationship with art was shaped primarily by personal passion and curiosity. Studying outside an art academy created a space where experimentation was possible without predefined expectations. Later, within academic art institutions, I became aware of how formal structures—while useful—can also limit personal and subversive experiences. This awareness continues to inform my curatorial and artistic work.”

Similar trajectories characterize other participants. Nikoo Alidoosti traces her engagement with photography to following a friend’s work on Facebook while studying law. Fatemeh Salehi’s background in urban planning informs her sustained attention to the city as a lived environment, while Morteza Beiglou emphasizes the formative influence of vocational art schools and darkroom spaces.

These discontinuities between formal education and artistic practice are not incidental. They reveal a structural condition shared by many independent practitioners: photography is maintained alongside other professions, functioning less as a career than as a sustained mode of engagement with lived reality.

Independent Middle-Class Art: A Structural Definition

To describe this condition, Forouzesh employs the term middle-class art. In this context, the term does not denote an average aesthetic or moderate artistic ambition. Rather, it refers to a structural position within the cultural field.

Independent middle-class art designates practices produced by artists who possess cultural capital—visual literacy, conceptual awareness, and historical sensitivity—without corresponding access to institutional power, economic resources, or symbolic legitimacy. These artists operate outside elite academic frameworks and global art markets, while also lacking the infrastructural support necessary for sustained visibility.

This position is defined by in-betweenness. Middle-class independent artists are neither fully integrated into dominant institutions nor positioned in radical opposition to them. Their marginality is not an aesthetic strategy, but the result of misalignment with prevailing systems of recognition, which tend to favor either institutionally credentialed practices or visually legible, market-oriented narratives.

Importantly, the middle-class condition remains analytically relevant because it shapes both the material conditions of production and the temporal rhythms of artistic work. These practices are often self-funded, developed over long durations, and sustained without guarantees of exhibition or circulation. Such conditions encourage attention to process, narrative accumulation, and personal experience rather than immediate visibility or performative impact.

Within this framework, the curatorial approach of The ORDINAЯY MOMENT consciously resists the category of the exotic. The notion of exoticism, long embedded in the Western reception of art from non-Western regions, presupposes a hierarchical gaze in which difference is aestheticized, simplified, and rendered consumable. By framing cultural otherness as spectacle, the exotic reduces complex social realities to visual markers of strangeness or cultural distance.

This curatorial project instead insists on proximity rather than distance. By foregrounding ordinary moments, personal narratives, and everyday temporalities, the exhibition rejects representational strategies that rely on cultural unfamiliarity or symbolic excess. In doing so, it positions the works not as illustrations of an “elsewhere,” but as autonomous artistic practices embedded in lived experience. Avoiding the exotic thus becomes an ethical and epistemological choice—one that seeks to suspend the unequal power relations often implicit in cross-cultural display and to allow the works to be encountered on their own narrative and formal terms.

The Camera as a Narrative Instrument

For the photographers in The ORDINAЯY MOMENT, photography functions less as a medium of representation than as a narrative instrument—a means of articulating personal relationships to time, place, and experience.

As Shervin Shirkubi notes:

“Sometimes I complain through photography, sometimes I protest, and sometimes I try to fix my own era in time. I rely on storytelling rather than manifestos.”

This emphasis on narrative aligns with Forouzesh’s broader research project, The [IN]VISIBLE Meaning, which examines the relationship between storytelling and meaning in photographic practice. Central to this inquiry is the question of whether photographic meaning resides solely in what is visible, or whether it is shaped equally by what remains unseen—including the photographer’s subjective position.

Within this framework, the act of selection becomes crucial. By isolating a single moment from countless possibilities, the photographer actively constructs narrative significance. The subject itself becomes secondary to the decision to record a particular fragment of lived reality.

Across the exhibition, photography is articulated as an inward process: a form of reflection, catharsis, or self-positioning. For Morteza Beiglou, it is a practice of patience; for Mahnaz Minavand, a means of approaching the self; for Fatemeh Salehi, a reciprocal dialogue with the world; and for Nikoo Alidoosti, a temporal suspension within an otherwise numbing reality.

Structural Constraints and the Politics of Visibility in Iranian Photography

The relative invisibility of these practices cannot be separated from the structural conditions of photography in Iran. Security restrictions, the high cost of equipment, and widespread public distrust toward cameras impose significant limitations on photographic work in public spaces.

Several photographers describe these constraints directly. Saeedeh Mirzadeh observes that many individuals actively avoid being photographed, while Mahnaz Minavand identifies the difficulty of street photography as a major obstacle to sustained practice. Nikoo Alidoosti notes that public resistance often interrupts the moment of documentation itself, resulting in the loss of what she describes as the “documentary moment.”

Beyond these material constraints, the photographers articulate broader critiques of Iranian photography’s relationship to international festivals and exhibition circuits. Shirkubi characterizes the field as entangled in imitation and repetition, arguing that it has yet to establish a fully autonomous visual language. Minavand points to the discouraging role of personal connections in gaining access to galleries, while Alidoosti critiques the prevalence of slogan-driven imagery that simplifies the complexities of contemporary Iranian life.

Within this context, independent middle-class practices occupy a particularly precarious position. International platforms often privilege images that conform to recognizable narratives of crisis, resistance, or cultural difference. Practices grounded in everyday experience, ambiguity, and personal narrative risk exclusion precisely because they resist such translation.

The Works Presented

The individual projects presented in The ORDINAЯY MOMENT reflect these concerns while maintaining distinct conceptual positions.

Nikoo Alidoosti’s The Fifth Wall engages critically with mediated empathy, drawing on Susan Sontag’s reflections on spectatorship and suffering. The series questions the assumption that distant observation constitutes ethical engagement, proposing the concept of a “fifth wall” produced by contemporary visual media.

Mahnaz Minavand’s Faceless emerges directly from lived experience, emphasizing anonymity and erasure as structural conditions rather than symbolic gestures. Shervin Shirkubi’s Streets, initiated in 2013, documents Iranian hip-hop culture through a long-term, uncensored engagement that resists both nostalgia and spectacle.

Morteza Beiglou recounts the making of a single image:

“I stood on the hot sand for an hour so this child could conquer the dune. Each time his feet burned, he knelt down. This patience exists in all my photographs.”

Such accounts foreground duration, presence, and commitment—qualities that align with the broader ethos of independent middle-class practice.

Photography in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

The expansion of AI-based image-making tools prompted reflection among the photographers on the future of photography. While acknowledging AI as a potential technical resource, participants consistently emphasized the irreplaceability of embodied experience.

Fatemeh Salehi likens AI to the early reception of photography itself: initially unfamiliar, but ultimately integrated into visual culture. Shervin Shirkubi, despite experimenting with AI, argues that the absence of sensory presence limits its capacity to convey human experience.

Forouzesh similarly emphasizes that the value of projects such as The ORDINAЯY MOMENT lies precisely in their grounding in lived reality—an element that remains resistant to automation.

Conclusion

The ORDINAЯY MOMENT articulates a curatorial position that foregrounds independent middle-class art as a vital yet underrepresented mode of cultural production. By focusing on photographers whose practices unfold outside dominant institutional and market frameworks, the exhibition challenges prevailing regimes of visibility and representation.

Rather than offering a unified thematic statement, the exhibition constructs a narrative of everyday life through accumulated personal perspectives. In doing so, it affirms the significance of artistic practices that privilege narrative integrity over recognizability, duration over immediacy, and lived experience over symbolic performance.

Projects such as The ORDINAЯY MOMENT suggest the possibility of alternative cultural structures—self-organized, sustainable, and attentive to the complexities of everyday life. They invite renewed attention to artistic practices that remain unseen not because of their insignificance, but because of their refusal to conform to standardized modes of representation.